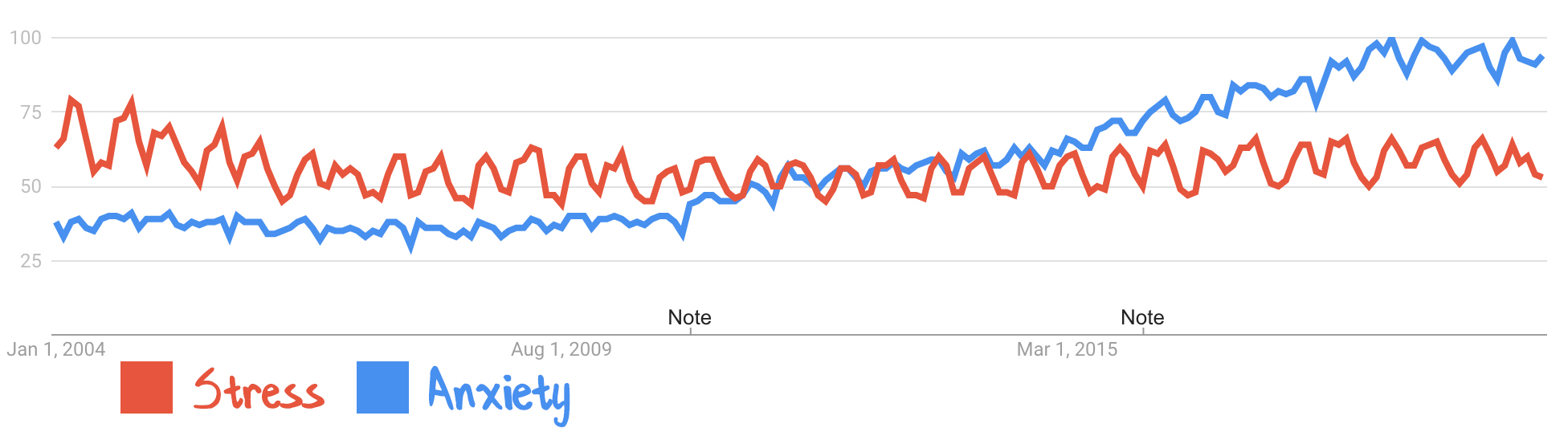

Before we discuss what causes stress, the intersection of stress and classroom instruction, and the general importance of understanding how stress works so that it may be appropriately addressed, I’d like you to consider the following linegraph:

This chart shows the Google search volume for two terms, STRESS and ANXIETY, over time. You’ll notice that in 2004, “stress” was searched for almost twice as often as “anxiety.” You’ll also notice that “stress” appears to oscillate — it peaks every November and April, and dips every January and July.

In comparing these search volumes over time, we can see a trend emerge that is as interesting as it is alarming. In 2012, “anxiety” overtook “stress” in search volume, and that trend has been increasing ever since.

The fundamental difference between stress and anxiety is that stress is the body’s response to some kind of a threatening situation, whereas anxiety is the body’s response to stress. This is important for us to keep in mind as we start to consider what causes stress, because it naturally raises a few more equally important questions: What happens when what causes stress doesn’t go away? And, what can we do to relieve stress?

It’s also important for us to realize that stress comes in many forms, and not all are equal. For our purposes here, let’s consider three brands of stress: the positive, the tolerable, and the toxic.

Positive Stress

POSITIVE stress is the kind of stress that makes an athlete perform at a higher level on the field, or that causes a procrastinator to get his or her work done. Much of this can be attributed to the body’s physiological reaction to stress. (Thanks, brain!) For teachers, this might be equated to a lift in performance when an observer walks into the classroom, because a touch of positive stress is enough to sharpen your senses, especially when engaging in something you’re good at. The same goes for a student who has been studying hard for a test, and who experiences an increase in performance on exam day.

Tolerable Stress

TOLERABLE stress is stress that doesn’t inherently grant us any immediate benefits. Rather, this is stress that we endure, like the loss of a loved one, the end of a relationship, or termination from a job. With the right supports in place, we can survive this kind of stress, and we might even emerge from it stronger and more resilient than ever before.

Toxic Stress

TOXIC stress is stress that is chronic, and that ultimately has ill-effects. When the stressors don’t go away, or when the proper supports aren’t in place to endure what may have otherwise been “tolerable,” that stress becomes toxic. Toxic stress shrinks the hippocampus (the part of your brain that stores long term memories), shrinks the prefrontal cortex (the part of your brain responsible for organization and impulse control, among other things), and enlarges the amygdala (causing increased sensitivity to “fight” and “flight”).

So from this high-level perspective, we might consider it a healthy mission to welcome positive stress for ourselves, and to encourage it for our students. We might also recognize the inevitability of certain kinds of stressors, and reframe those experiences to better develop resilience and grit. And, finally, we should recognize that toxic stress is as real a problem as any, with real implications that quite literally affect the physical structures in our brains. Toxic stress can impede your ability to teach, and your students’ abilities to learn. It can impede your ability to plan a lesson (and, frankly, to manage the rest of your life), and your students’ abilities to complete their assignments (and, also frankly, to manage the rest of their lives).

Understanding what causes stress will put you in a significantly better position for managing your own life and career (cue the trending articles about teacher burnout), as well as for better supporting your students as they navigate an increasingly stressful world.

What Causes Stress: Four Factors

The neuro and cognitive science points us to four elements regarding what causes stress. These factors are:

- Novelty. If a situation has never been experienced before, it’s likely to induce some degree of stress. If we think of stress as something our bodies have learned to “do” in order to give us an evolutionary advantage, this can make a lot of sense. If our ancient ancestors encountered a new kind of animal, or berry, or weather pattern, for the first time, it likely produced a stress response that was beneficial to their survival. It either optimized their performance (flight, e.g. “Let’s get the heck away from this thing,” or fight, e.g. “Smash it!”).

- Unpredictability. Whether or not a situation is novel, stress can stem from unpredictability. Are the outcomes of any given scenario, novel or not, known or unknown? Are the parameters, rules, and byproducts certain or uncertain? A more concrete example might be the question of whether or not it might rain on the day of an important outdoor event. That feeling of unpredictability can certainly be stress-inducing, and the higher the stakes of that outdoor event (an informal barbeque vs. a wedding ceremony), the greater the stress.

- Harm to Body or Ego. This is perhaps the most obvious factor. Stress is induced if a person’s safety is challenged for any reason, whether it is a threat to the body or the ego. Will a tornado in the distance stress you out? You bet it will. Will a public performance in which you’re likely to look foolish also stress you out? Of course.

- Lack of Control. Control is so interesting because it’s really at the center of what causes stress. If anyone feels like they aren’t in control of a situation, or like they’re just waiting for the inevitable to occur despite their desire for something else, they will feel stress. But here’s the interesting part: the opposite is also true. To paraphrase distinguished neuroscientist Steve Maier, “the perception of control inoculates from the harmful effects of stress.”

What Causes Stress in the Classroom

Let’s take a moment to use the four factors that we’ve identified as what causes stress as a lens for considering the classroom environment and instructional practices.

- Is it novel? Typically, students benefit from a significant amount of structure and routine. They know the rules of “school,” and the learning environment is often one they’re accustomed to. But, occasionally, that routine is upended — for example, when students start a new school (e.g. entering into middle school or high school), start a new bell schedule, or explore a content area outside of their comfort zones. Similarly, the content and skills that are taught in class can be considered “novel” in that they’re new — but that “novelty” can be tempered by activating prior knowledge and ensuring that students have the foundational understandings necessary to learn the upcoming content. This can be the difference between an engaged learner experiencing “positive stress” and a disengaged learner who associates anxiety with a given unit, class, or teacher.

- Is it unpredictable? In short, the more transparent the learning process is, the better. Are students aware of the intended learning outcomes? Are the instructions for the assignment clear? Is the rubric and any associated grading criteria crystal clear? A good rubric goes a long way in alleviating the stress associated with some of the most challenging assignments simply because they introduce an element of predictability that students can use to hone their expectations.

- Is anything threatening? This is a tricky one, because students can feel threats to their egos from some very subtle places. The obvious threats (e.g. a classroom bully, a threat to bodily harm) are usually clear, whereas the threat of misreading a word in front of one’s peers is tougher to pinpoint. Instructional decisions that prioritize students’ feelings of safety (like eliminating the practice of “cold calling”) can go a long way for reducing stress.

- Do students feel a sense of control? We talk a lot about the importance of student choice, the benefits of which are well documented. Greater choice leads to greater student agency, and higher levels of student engagement. But what happens when choice is absent? Consider the following scenarios:

- A student must complete an assignment as described in the instructions, with no latitude for how they demonstrate understanding.

- A student isn’t given any choice in the matter of what is being learned in class. Instead of making authentic connections to the content, the student feels like “it’s only being learned because it’s in the approved curriculum.”

- A student earned a zero on an assignment, and regardless of how hard they work moving forward, their marking period grade is detrimentally affected.

- A student arrives to school late every day because her single-parent works the night shift and doesn’t make it home in time to get her younger sibling on the bus.

Some of these scenarios can be easily remedied with instructional design choices that promote choice and that differentiate learning for students. Others require deeper philosophical shifts (i.e. should a “zero” ever actually be a “zero” on a 100 point scale?). And others still feel inevitable, beyond our control as the teachers in the room. These scenarios, like the student whose home life makes her feel like she is doomed to fail in school, are the most challenging — and are the scenarios where our efforts are most valuable. There is tremendous power in simply having an open and honest conversation with a student, of offering choice and flexibility, of making him or her feel safe and empowered, and of making the appropriate resources available.

For practical and proven strategies that promise to relieve stress for yourself and for your students, check out our post on how to relieve stress!

Go Deeper With These Books!

Much of what has been described here has been summarized from some of the following books on stress, learning, and children. If you’re interested in learning more, definitely consider jumping into some of these titles — they’re GREAT.

- The Self-Driven Child: The Science and Sense of Giving Your Kids More Control Over Their Lives by William Stixrud and Ned Johnson.

The last time I heard Stixrud speak, he talked so much about the power of giving students a sense of control — which is aligned with everything we know about stress. He also opened by emphasizing that the top three leading causes of stress related mental health issues were poverty, trauma, and discrimination. The fourth? Excessive pressure to excel.

- The Price of Privilege: How Parental Pressure And Material Advantage Are Creating A Generation Of Disconnected And Unhappy Kids by Madeline Levine

Madeline Levine and Denise Pope (author of Overloaded and Underprepared) have both been doing quite a bit of work around the negative effects of stress, particularly on populations that are otherwise high achieving. If that sense of “excessive pressure to excel” is something that hits close to home, you might want to check them both out!

- Born Anxious: The Lifelong Impact of Early Life Adversity – and How to Break the Cycle by Daniel Keating

Keating dives into some really profound findings about the effects that the stress hormone cortisol can have (on humans, and on rates) when high levels of chronic stress are experienced. High levels of stress at an early age can create “lifelong, unrelenting stress and its consequences – from school failure to nerve-wracking relationships to early death.” If you’re interested in some of the most recent scientific findings on stress (what happens when rat pups aren’t groomed by their mama, versus when they are?) and an insightful discussion of nature versus nurture (spoiler: they’re both significant players), pick this one up!